Moscow has certainly been a flurry of diplomatic activity in recent days. Jan. 13 saw the first direct meeting in years between the intelligence chiefs of Turkey and Syria’s Assad regime, supposedly deadly rivals. The head of Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (MIT) Hakan Fidan met with Ali Mamlouk, head of the Syrian National Security Bureau, in a sure sign of a Russian-brokered rapprochement between the burgeoning dictatorship of Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the entrenched dictatorship of Bashar Assad. Sources said discussions included “the possibility of working together against YPG, the terrorist organization PKK’s Syrian component, in the East of the Euphrates river.” (Daily Sabah, Reuters)

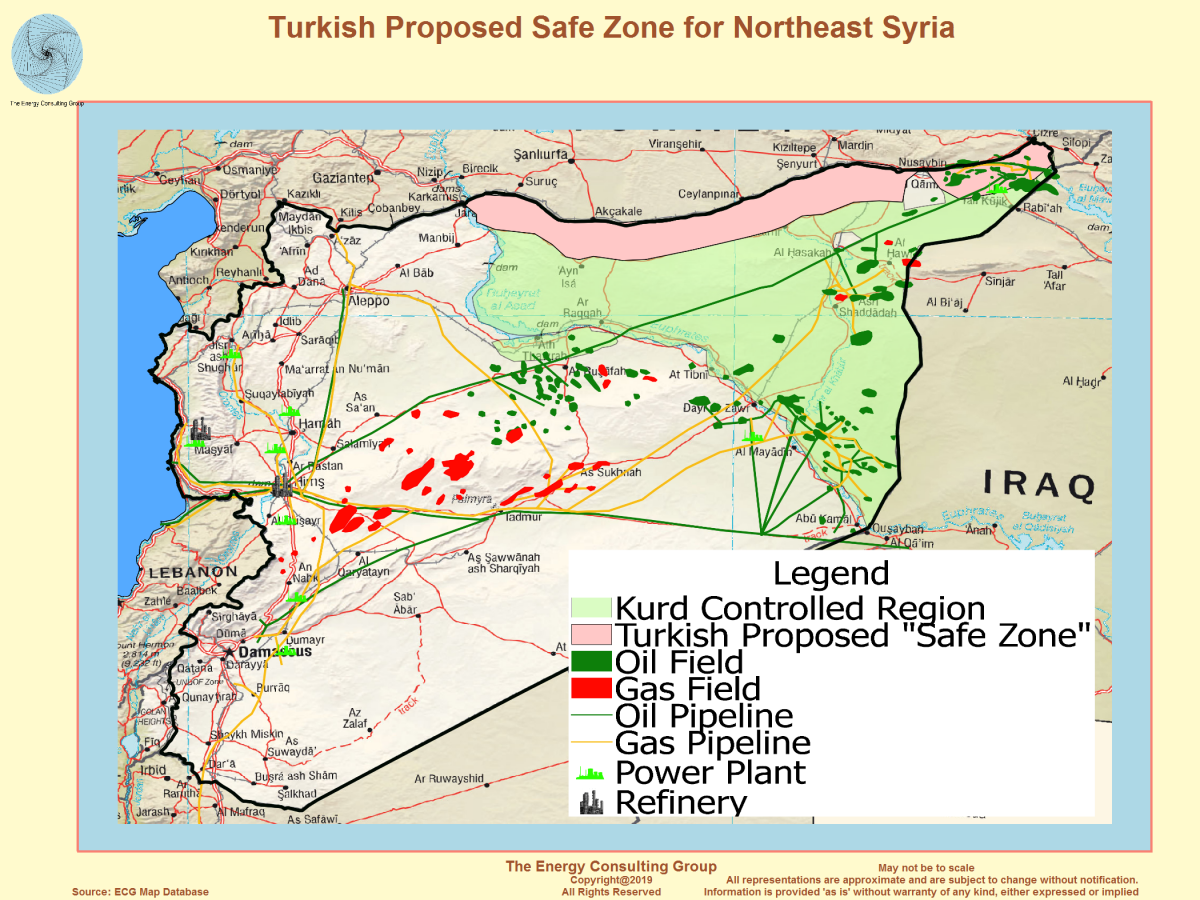

This is a reference to the People’s Protection Units (YPG), the Kurdish militia in northern Syria, which is ideologically aligned with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the banned Kurdish revolutionary organization operating in Turkish territory. The Euphrates River had been a border between Turkey’s influence zone in Syria to the west and the Kurdish autonomous zone to the east—until Turkish forces crossed the river and invaded the autonomous zone last year. In response, the YPG made a separate peace with the Assad regime to resist the Turkish advance. It should come as little surprise that Assad is now evidently considering their betrayal in exchange for some kind of peace with Turkey.

Also in Moscow on Jan. 13 was Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar, who reportedly rejected Moscow’s effort to get him to halt his offensive on Tripoli and agree to a ceasefire. (DW) This comes as Turkey is preparing military intervention in Libya to back up the Tripoli government against Haftar, who has been supported by Russia.

Russia and Turkey have long been regional rivals, backing opposing sides in Syria and Libya alike. Now that they appear to be converging into a single regional power bloc (after nearly going to war with each other just four years ago), getting their respective clients and proxy forces to get along will clearly be a challenge.

The diplomatic meetings in Moscow come just as Russia officially opened its TurkStream gas pipeline, delivering natural gas under the Black Sea to Turkey—and strategically bypassing Ukraine. The pipeline was put on hold during the mutual tensions between the two powers.

Now it is pumping to Turkey and Bulgaria, with extensions foreseen to Serbia and Hungary. Construction of another major Russian pipeline, the Nord Stream 2 link under the Baltic Sea, was halted last month after the US slapped sanctions on the contractors building the line to Germany. The Nord Stream link was similarly designed to bypass Ukraine. (Bloomberg, BBC News)