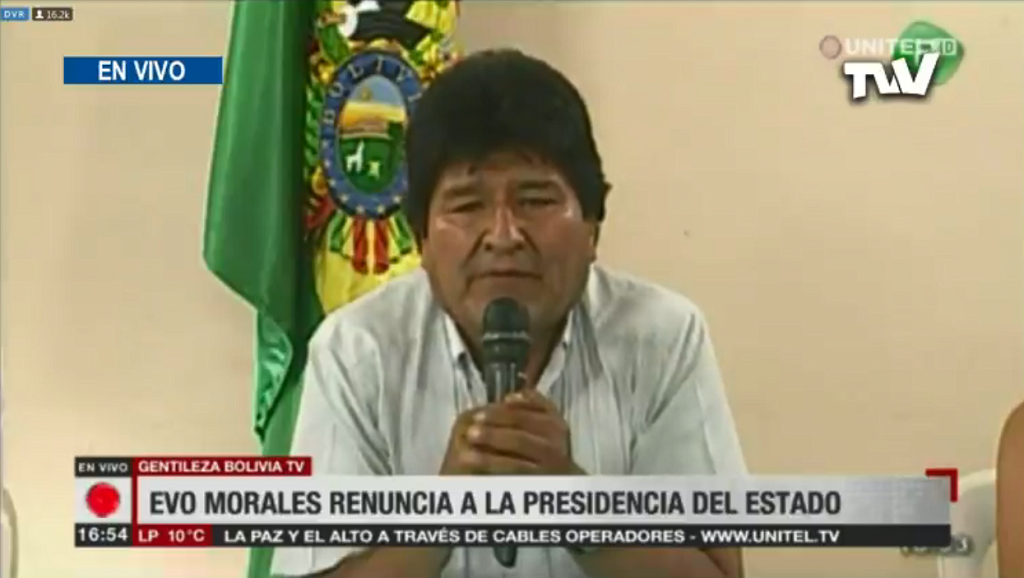

On Nov. 10, Bolivia’s besieged president Evo Morales flew from La Paz to the provincial city Chimoré in his traditional heartland of Cochabamba department, where he issued a televised statement announcing his resignation. The statement decried the “civic coup” that had been launched against him, noting more than two weeks of increasingly violent protests since last month’s disputed elections. He especially called on Carlos Mesa, his challenger in the race, and Luis Fernando Camacho, the opposition leader in the eastern city of Santa Cruz, not to “maltreat” the Bolivian people, and “stop kicking them.” He vowed that the fight is not over, and that “we are going to continue this struggle for equality and peace.”

His vice president Álvaro García Linera also issued a statement, saying “the coup has been consummated.” But he also pledged a continued popular mobilization by Morales supporters. Invoking the words of the 18th century Aymara revolutionary Túpac Katari, he said, “We will return, and we will be millions.”

The opposition also pledged to keep up the pressure. “Today we won a battle,” Camacho told a crowd of cheering supporters in La Paz as Morales fled the city. But he also demanded that all lawmakers (senators and lower-house deputies), high court magistrates, and members of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal also resign. “Only when we can be sure that democracy is solid, then will we go back home.”

Morales’ resignation came hours after the OAS issued a statement on preliminary findings of its audit of the Oct. 20 vote, stating that the results should be “annulled and the electoral process should begin anew as soon as new conditions exist that give new guarantees for its execution, including a new composition of the electoral organ.” The accompanying OAS report found that 350,000 votes are called into question by irregularities in the computer system—far more than the 40,000 by which Morales ostensibly won. “The manipulations to the computer systems are of such magnitude that they must be deeply investigated by the Bolivian State to get to the bottom and assign responsibility in this serious case.”

After the statement was issued, several Morales allies resigned, including Mining Minister Cesar Navarro and Chamber of Deputies president Victor Borda—who both cited fear for the safety of their families. Juan Carlos Huarachi, leader of the Bolivian Workers Confederation (COB), also called on Morales to step down “for the health of the country.”

Joining calls for Morales’ resignation was Gen. Williams Kaliman, commander of the armed forces, who said the president should step aside “for pacification and the maintaining of stability, for the good of our Bolivia.”

Another Morales ally, Senate leader Adriana Salvatierra, also stepped down. This cleared the way for the Senate vice-president, Jeanine Añez of the opposition Social Democratic Movement (Demócratas), to become the new leader of the upper house—and next in line in the presidential succession. After the resignation of Moraels and García Linera, she announced that she is to become interim president until new elections can be held. Añez is one of Morales’ harshest opponents. (Los Tiempos de Cochabamba, Los Tiempos, PaginaSiete, La Paz, FM Bolivia, BBC Mundo, BBC Mundo, BBC News, Reuters, InfoBae, InfoBae, Argentina, La Republica, Ecuador, RPP Noticias, Peru, Nov. 10)

Police mutiny, escalating violence

In the 48 hours leading up Morales’ resignation, police forces in four Bolivian cities declared themselves to be in “mutiny” against the government, and joined the opposition protests in the streets. The first to announce rebellion was the Cochabamba detachment of the elite Special Operations Tactical Unit (UTOP). National Police commanders in Santa Cruz, Sucre and Tarija shortly followed. (RPP Noticias, Peru, Nov. 8)

This came amid growing violence across the country. In Oruro, an angry mob on Nov. 9 burned the house of the departmental governor Victor Hugo Vásquez, a Morales ally. The home of the city’s mayor, Saúl Aguilar, another Morales ally, was also set on fire. He announced his resignation shortly after the attack, and joined the calls for new elections. (La Razon, La Paz, Nov, 10; La Razon, Nov. 9)

On Nov. 6, a mob set fire to the municipal building in Vinto, a town in Cochabamba department, and dragged out the mayor, Patricia Arce, again a Morales ally. She was forcibly marched through the streets, while the assailants sprayed her with red paint and cut her hair. She was eventually rescued by the police. That same day, in the nearby village of Huayculi, a young man named Limbert Guzmán Vásquez, apparently a Morales supporter, was beaten to death by a mob. (Los Tiempos, Nov. 8; EFE, BBC News, Nov. 7; Ambito, Argentina, Nov. 6)

On Oct. 30, two men were killed in Montero, a town outside the city of Santa Cruz, in clashes between supporters and opponents of Morales. Both were apparently Morales opponents, and died of gunshot wounds. (BBC News, InfoBae, Oct. 31; Eju!, Santa Cruz, Oct. 30)

Amid the left-right polarization, an indigenous opposition to Morales also mobilized. Lawmaker Rafael Quispe, a traditional Aymara leader from La Paz department and a former Morales supporter, on Nov. 7 announced the start of a hunger strike to demand the president’s resignation. In a statement from the Chamber of Deputies building, where he held the fast, he called for “a halt to confrontation,” but also demanded that the entire Supreme Electoral Tribunal step down along with Morales. (Pagina Siete, Nov. 7)

OAS findings contested

There has been dissent to the OAS findings that the Oct. 20 election was tainted. The initial OAS statement the day after the vote stressed the hiatus in the count after it began to indicate that the race would have to go to a second round. Twenty-four hours later, the count was resumed, “with an inexplicable change in trend that drastically modifies the fate of the election and generates a loss of confidence in the electoral process.”

But Mark Weisbrot, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) in Washington, issued his own analysis contesting that of the OAS. “The OAS statement implies that there is something wrong with the vote count in Bolivia because later-reporting voting centers showed a different margin than earlier ones,” Weisbrot said. “But it provides absolutely no evidence—no statistics, numbers, or facts of any kind—to support this idea. And in fact, a preliminary analysis of the voting data at all of the more than 34,000 voting tables—which is all publicly available and can be downloaded by anyone—shows no evidence of irregularity.” He called on the OAS to “retract” its statement.

In a Nov. 9 interview with the BBC, Weisbrot called the claims of electoral fraud “nothing, at this point, more than an unfounded conspiracy theory.” He said the OAS is “under enormous pressure from the Trump administration and Senator [Marco] Rubio, who have publicly stated their intentions to also get rid of this government.”

Arrest orders for Morales?

Hours after Morales announced his resignation, the recently resigned president and vice president of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, María Eugenia Choque and Antonio Costas, were both arrested in La Paz. (ABI, Nov. 10)

Nearly simultaneously, Morales reported on Twitter that his home in Cochabamba had been attacked by a mob of opponents, and that he had received word that arrest orders have been issued against him. “The coup-mongers are destroying the rule of law,” he said. (Los golpistas destruyen el Estado de Derecho.) (ABI, Nov. 10)

Photo: Unitel.tv

Bolivia: was it a ‘coup’? And will it be war?

While the gringo lefties (such as, inevitably, Noam Chomsky) are rushing to call it a “coup,” voices on the left in Bolivia and South America provide a more nuanced assessment.

The Uruguayan writer Raúl Zibechi warns of “A Popular Uprising Exploited by the Ultra-Right.” (In English here, and in Spanish here.) He notes that as well as the COB, another major trade union, the Syndical Federation of Mine Workers of Bolivia (FSTMB) had also stated: “President Evo, you have done much for Bolivia, you have improved education, health, and brought diginity to many poor people. President, do not allow your people to burn, don’t allow more deaths to go on being president. All the people will value you for the position you must take; resignation is inevitable, compañero President. We must leave the national government in the hands of the people.”

He also notes Morales’ alienation of former indigenous allies now in the opposition, such as Rafael Quispe’s organization CONAMAQ. Zibechi concludes:

Another dissident analysis is offered by Pablo Solón of the Fundación Solón in La Paz, Morales’ former UN ambassador but today in the left opposition. (English here, Spanish here.) He asks flatly, “What happened in Bolivia? Was there a coup?” He also warns of right-wing exploitation of the crisis, but does not exculpate Morales of fraud, and calls him to task for serious errors.

First he notes that the company contracted by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal itself to review the election results found that the process was “nullified by corruption” [viciado de nulidad]. (An account in Argentina’s La Nación identifies the company as the Panamanian firm Ethical Hacking, although, confusingly, another account on DW has the Tribunal pointing to the Ethical Hacking review as vindicating the results.) Solón charges that the Morales government “minimized the indignation generated by the fraud. In the beginning, Evo Morales said the protests were small groups of youth tricked by money…”

In an interview with Solón by Britain’s Political Economy Research Centre, he elaborates on the deeper long-term strategic errors by Morales and his party:

Another neither/nor perspective is offered by Maria Galindo of La Paz feminist collective Mujeres Creando (in English here and Spanish here). First, she repudiates the version of events proffered by Morales and his supporters:

But next she turns to right-opposition leader Fernando Camacho:

Meanwhile, on the subject of the “game of war” warned of by Zibechi, frightening footage has emerged on social media (see here, here and here) of Morales’ most militant supporters, the Ponchos Rojos, running through the streets in El Alto with wiphala flags, setting off dynamite, and chanting “Now yes, civil war!” (it sort of rhymes in Spanish:¡Ahora si, guerra civil!) and “Rifle, machine-gun, El Alto will not fall!” or “El Alto will not be silent!” (The Spanish can be translated either way: ¡Fusil, metralla, El Alto no se calla!)

More at No Borders blog.

Anti-indigenous ugliness in Bolivia

In further signs of dnagerous polarizarion, Adriana Guzmán of the groups Feminismo Comunitario Antipatriarcal de Bolivia (Community of Anti-Patriarchal Feminism of Bolivia) and Feministas de Abya Yala (Feminists of Mother Earth) asserts in an interview (in English here and Spanish here) that right-wing mobs (“militias,” she calls them) are burning the wiphala, the rainbow flag of the indigenous movement, in the streets of La Paz. She also (it should be noted) at least questions the wisdom of Evo’s presidential run.

TeleSur has meanwhile dug up an April 14, 2013 tweet from the new self-declared president Jeanine Añez (then a senator from Beni, in the eastern lowlands), in which she wrote (translated from Spanish): “I dream of a #Bolivia free of Indigenous satanic rites, the city is not for ‘Indians,’ they better go to the highlands or El Chaco.”

Update: We note that Bolivian news site Página Siete is tweeting that Añez’s racist tweet is a fabrication. But others have responded with an archived tweet from Añez on Aug. 15, 2013, in which she appears to respond to the Aymara New Year celebration (which would have been almost two months earlier, on June 21) by calling it “Satanic.”

We honestly don’t know what to believe at this point.

It is clear that Añez entered the presidential palace on Nov. 12 prominently brandishing a huge leather-bound Bible, and the next decalred (in case this symbolism was lost on anyone) that "the Bible has returned to the palace." (Fox News, Bloomberg) This is a rather unsubtle rejection of the "Pachamama" talk under Evo Morales.

SOA fingerprints on Bolivia ‘coup’?

A tweet from SOA Watch informs us that the Bolivian armed forces commander now being portrayed as the decisive voice in forcing Evo Morales from power, Gen. Williams Kaliman, took a course at the WHINSEC (formerly the School of the Americas) in “Command and General Staff” in 2003.

A commentary in Argentina’s left-wing Notas, portraying Kaliman as a turncoat, recalls that he in the past called Morales “brother” and declared himself to be a “soldier in the process of change.” On Aug. 7 of this year, he declared: “We were born in the struggle against colonialism and we will die anti-colonialist, because it is our pride and our reason for life… The armed forces belong to the people and work for the people, because we support the nationalization of hydrocarbons and state policies that favor the most needy.” This was in the context of Morales’ announcement that he would seek to covert his Anti-Imperialist Military School (conceived in 2016 as a counter-weight to the SOA) into a “Command of the South,” to defend the interests of Latin America.

Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui speaks on Bolivia ‘coup’

Bolivian anarcho-feminist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui speaks at a “Parliament of Women” convened in La Paz by Mujeres Creando, and posted to YouTube. She says: “I don’t believe in the two hypothoses…. This juncture has left us with a great lesson against triumphalism… The triumphalism that with the fall of Evo we have recovered democracy… The second incorrect hypothesis that seems to me to be extremely dangerous is the hypothesis of the coup d’etat that simply wants to legitimize—completely, with the full package, wrapped in cellophane—the entire government of Evo Morales in its moments of greatest degradation… to legitimize this entire degradation with the idea of the coup d’etat is criminal… I have great pain over what has happened, I have no sense of triumph… But the defeatism that says that there is a coup here and that everyone has lost is false. It is to think that MAS is all we have as a possibility for inter-ethnicity, pluriculturality… I am with the wiphala, compañeras, but there are many classes of wiphala, there isn’t just one.”

Thanks to Jane Guskin for translation help.

Note: For some reason the Silvia Rivera interview was removed from its original location, but can now be found here….

‘Evo lost Evo’

Another analysis from Raúl Zibechi on DesInformemonos, entitled “Evo perdió a Evo” (Evo Lost Evo), notes that the Qhara Qhara Nation indigenous group in Potosí had joined the call for Evo Morales to resign, issuing a “manifesto” that read in part (our translation):

Chiquitanía is the region of Bolivia’s lowlands devoured by forest fires this year. Chaparina is the site of repression of indigenous protesters during the 2011 cross-country march against the road to be built through the TIPNIS indigenous reserve. Tariquía is a nature reserve in Tarija department recently opened to gas exploration, sparking local protests (see The Ecologist, June 24)

Questions on Bolivia’s presidential succession

Aristegui Noticias is reporting claims by MAS Senate leader Adriana Salvatierra that she did not in fact resign, but that her way into the Plurinational Legislative Assembly building on Nov. 13, where she had sought to clarify the matter, had been barred by police roadblocks.

PaginaSiete also notes claims by Susana Rivero, the MAS head of the lower house Chamber of Deputies, had been improperly passed over in the succession. Both Salvatierra and Rivero have now taken refuge in the Mexican embassy.

These claims cast doubt on Añez’s claim to presidency on the basis of succession.

MAS lawmakers has called a meeting of Legislative Assembly to discuss Moarles’ resignation Nov. 19—raising the possibility that they could vote to reject it. However, they instead issued a statement at the last minute saying the meeting had been postponed. (Reuters) Perhaps this was done to evalute the claims of Salvatierra and Rivero.

Uruguay has announced that it will not recognize Añez’s presidency. (Conclusion)

AFP meanwhile has poduced a much-needed fact-check on Añez’s racist tweets. Yes, the one about indigenous “satanic rites” is a fabrication (and we await TeleSur‘s retraction), but the one about the “satanic” Aymara new year was real (although later deleted), and the actual date was a more logical June 20, 2013.

Finally, Capitalism, Nature, Socialism has published an essay by Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, entitled “Evo and the Movements: A Long Process of Degradation.” She writes: “The movements who were initially the president’s support base were divided and degraded by a left that would allow only one possibility and wouldn’t allow autonomy.”