Yemen: next in GWOT cross-hairs

British Prime Minister Gordon Brown and US President Barack Obama have agreed to fund a special counter-terrorism police unit in Yemen to tackle the rising threat from the country.

British Prime Minister Gordon Brown and US President Barack Obama have agreed to fund a special counter-terrorism police unit in Yemen to tackle the rising threat from the country.

by David L. Wilson, MR Zine

Congress is almost certain to consider some sort of reform to the immigration system in 2010; when it does, we can expect a repeat of the “tea bag” resistance we saw at last summer’s town halls on healthcare reform. The healthcare precedent “bodes badly” for immigration, Marc R. Rosenblum, a senior policy analyst at the DC-based Migration Policy Institute, told a forum at Columbia University in New York City the evening of December 1.

Unfortunately, the discussion that night indicated that progressives are planning to follow the same scenario we followed in the struggle for healthcare: we propose legislation that falls short of what we need, the right wing then whittles it down, and in the end we are told we have to be responsible and accept half a loaf—or a good deal less than half.

What makes it worse is that, if we follow this plan, we will probably lose a unique opportunity to have a lasting effect on the way people think about immigration in this country.

The “Three-Legged Stool”

Most proposals for “comprehensive immigration reform,” or “CIR,” conform to the “three-legged stool” concept that Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano outlined in a speech on November 13. Each “leg” is meant to appeal to a different constituency:

* for the country’s 12 million undocumented immigrants, CIR offers a limited legalization program;

* to satisfy the immigration restrictionists, the package expands the enforcement of immigration laws;

* to keep the corporations happy, the legislation includes a mechanism for bringing in foreign workers.

Rep. Luis Gutierrez (D-IL) introduced one version of this on December 15. His bill, CIR-ASAP, sets up an “earned legalization” process for out-of-status immigrants and eliminates some of the worst abuses of the current system—the lack of proper medical attention for immigration detainees, for example, and the 287(g) program that brought local sheriff’s offices into immigration enforcement. At the same time, it expands more “humane” enforcement methods, like the E-Verify program, which requires employers to use a government database to check every job applicant’s immigration status.

For the corporations, the bill sets up an independent bipartisan “Commission on Immigration and Labor Markets” to determine when and how much to increase the flow of foreign workers for different industries. This proposal, which is backed by the Migration Policy Institute and the AFL-CIO, includes labor rights protections that would cut down many of the abuses in the present H1 and H2 guest worker programs.

The Gutierrez bill has a number of attractive features. Its big flaw is that it’s not going to pass.

A bill along these lines is never going to placate the restrictionists and the employer associations. The restrictionists won’t be satisfied because an expanded E-Verify program won’t stop people from coming here to look for work; it will just drive more of them to work off the books or with shady subcontractors. And the corporations won’t be satisfied because they don’t want labor commissions—they want a guest worker program, preferably with as few labor protections as possible.

“If the unions think they’re going to push a bill through without the support of the business community, they’re crazy,” Randel Johnson, U.S. Chamber of Commerce vice president of labor, told the New York Times last April. “As part of the trade-off for legalization, we need to expand the temporary worker program.”

Welcoming the Debate

The restrictionists and corporations will of course follow the healthcare scenario once the CIR debate gets under way, mobilizing their right-wing bases and pouring tens of millions of dollars into lobbying. The results are predictable: an immigration bill with more enforcement and a larger guest worker program. The only question is whether legalization will go the way of the public option.

That is, if we stick to the script. But we don’t have to.

Instead of acting out a rerun of the healthcare compromise, devoting resources to lobbying and focusing on arcane points of parliamentary procedure, the grassroots movement for immigrants’ rights needs to take the issue out to the population at large. This after all will be one of the rare occasions when people are actively thinking about immigration; and the economic crisis means they will be more open than usual to new and radical ideas.

But we’ll need to state our position clearly and forcefully, without apologies and equivocations, and we’ll have to take the discussion directly to the union hall, the community center, and the classroom, bypassing the controlled “debate” in the corporate media. Above all we’ll need to come right out and say what many immigrant rights advocates have been strangely reluctant to say in the past: immigration reform isn’t just good for immigrants—it’s good for everyone who has to work for a living.

It’s not as if the arguments from the right are so hard to defeat. We know what the anti-immigrant groups will say: the 1986 amnesty encouraged more immigration; legalization now will mean millions of new workers competing for jobs at a time of double-digit unemployment. But we’ll have no problem answering this, since it’s simply not true: there’s no evidence that undocumented immigration increased because of the 1986 amnesty. The fact that right-wingers have gotten away with saying this for two decades just shows their ignorance and dishonesty—and our own unwillingness to confront them.

The reality is that, by ensuring labor rights for immigrant workers, legalization will help “end the race to the bottom” and create an upward pressure on wages. “If you want to fix the economy, part of the way to fix it is legalization,” Frank Sharry, president of the pro-reform America’s Voice, said at the December 1 forum. “I welcome the debate.”

Confronting Enforcement

It’s encouraging that many liberals are finally starting to make this argument around wages, and we should push them to keep up the good work. But they’re not “welcoming the debate” when it comes to enforcement. As Marc Rosenblum noted in an email, “even most progressive lawmakers are pretty heavily invested in the sanctions approach.”

We don’t need to follow them on this. Nothing stops people at the grassroots from pointing out that the tens of billions of dollars spent on enforcement over the past 25 years have done next to nothing to slow the flow of undocumented immigrants; their real accomplishment has been driving down wages and sabotaging union organizing.

A 1999 study by Columbia University economist Francisco L. Rivera-Batiz indicates that the “employer sanctions” instituted in 1986—as part of a “trade-off for legalization”—almost immediately forced wages down for undocumented workers. And last October the AFL-CIO and other groups put out a report showing how the effect of enforcement at the workplace has been “chilling the assertion and exercise of workplace rights, a result that hurts all workers, regardless of immigration status.”

We need to make these arguments, and we also need to say that there’s no real way to slow down immigration without addressing its root causes, the political and economic situation in the countries to our south—and that to a large extent this situation is the product of economic policies like NAFTA that are promoted by the U.S. elite.

If people who claim to be concerned about the pace of migration are really serious about addressing the issue, they can join with us in supporting struggles against “free trade” agreements in South America, or in solidarity with the 42,000 laid-off electrical workers in Mexico City, or the Honduran unions fighting last June’s coup d’état. They can back the movement for the “right not to migrate,” Mexicans organizing for “development that makes migration a choice rather than a necessity,” in the words of University of California Los Angeles professor Gaspar Rivera Salgado. And they can support the efforts of leftist governments in Bolivia and Ecuador to use economic incentives to get migrants to come home.

The Trail of Dreams

Can immigrants win a New Deal in 2010? That will depend on a lot of things. One will be the impact of mobilizations by immigrants and their allies—not just the large protests but also small dramatic actions like the “Trail of Dreams,” a 1,500-mile walk a group of Florida students are starting on January 1. But another factor will be how vocal and effective we are in presenting the issues behind the mobilizations. If we do the job right, we’ll at least be able to weaken the influence of the anti-immigrant “tea parties,” and we’ll start to change the terms of the debate. Under the right circumstances, we might even build enough pressure on Congress to get a real immigration reform.

—-

This article first appeared, with footnotes, Jan. 1 in MR Zine.

Sources:

Julia Preston Napolitano, “White House Plan on Immigration Includes Legal Status”

New York Times, Nov. 13, 2009

Randal C. Archibald, “New Immigration Bill Is Introduced in House”

New York Times, Dec. 15, 2009 (A summary of the bill is at the ACLU website.)

Michelle Chen, “Troubled ‘E-Verify’ Program Highlights Dysfunctional Immigration System”

In These Times, Sept. 14, 2009

Julia Preston and Steven Greenhouse, “Immigration Accord by Labor Boosts Obama Effort”

New York Times, April 13, 2009

David L. Wilson, “The Truth about Amnesty for Immigrants”

MRZine, Aug. 8, 2009

James Parks, “Report: Unbalanced Immigration Enforcement Hurts All Workers’ Rights”

AFL-CIO Blog, Oct. 27, 2009

Amy Traub, “Getting Tough on Exploitation”

The Nation, Nov. 17, 2009

“NAFTA Boosted Mexican Immigration: Study”

World War 4 Report, Jan. 24, 2009

David L. Wilson, “Mexican Layoffs, U.S. Immigration: The Missing Link”

MRZine, Nov. 22, 2009

David Bacon, “The Right to Stay Home—Derecho de no Migrar”

New America Media, July 8, 2008

“Bolivia: Government Wants Immigrants Back”

Weekly News Update on the Americas, Dec. 27, 2009, also at World War 4Report

“Correa pide a emigrantes regresar”

El Universo, Guayaquil, Ecuador, March 24, 2009

Jane Guskin and David L. Wilson, “A Grassroots Vision for U.S. Immigration Policy—and Beyond”

NACLA Report on the Americas, January-February 2009

See also:

AMNESTY NOW: HOW AND WHY

by Jane Guskin, Huffington Post

World War 4 Report, April 2009

THE GREAT WALL OF BOEING

Corporate Power and the Secure Border Initiative

by David L. Wilson, MR Zine

World War 4 Report, October 2008

From our Daily Report:

Arizona: anti-immigrant sheriff vows defiance of feds

World War 4 Report, Oct. 19, 2009

——————-

Reprinted by World War 4 Report, January 1, 2010

Reprinting permissible with attribution

Why It Is On the Rise

by Gilbert Achcar and Pierre Puchot, Mediapart

What pushes Arabs to deny the existence of the Holocaust? How and why does Israel continue to instrumentalize the memory of the destruction of European Jewry? What was the attitude of Arab intellectuals during the Second World War? Why does Iran’s Mahmoud Ahmadinejad incessantly brandish the denial weapon while Hamas and Hezbollah turn away from it? In his new book, Les Arabes et la Shoah (The Arabs and the Holocaust), political scientist Gilbert Achcar—professor at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS)—reviews over a century of history from the birth of Zionism to last winter’s Israeli offensive against Gaza. Although he gives prominence to the political impasse constituted by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he indicates “new links” that today exist between Jews and Arabs.

Les Arabes et la Shoah is published in French by Actes Sud/Sindbad, and will be published in English by Metropolitan Books later this year. This interview with Pierre Puchot of the French online journal Mediapart ran along with an excerpt from the book in October.

Pierre Puchot: Your book’s subtitle is: “The Israeli-Arab War of Narratives.” What do you mean?

Gilbert Achcar: It’s about the war that opposes two entirely symmetrical visions of the origins of the conflict. Specifically, I refer here to the notion of “narrative” as the recitation of history as developed by post-modernism. The Israeli narrative describes an Israel that emerges as a reaction to anti-Semitism, beside the “Biblical rights” invoked by religious Zionists. And its justification by European anti-Semitism is extended to Arabs, who are presented as accomplices to this paroxysm of anti-Semitism that was Nazism—which would legitimate the birth of the State of Israel on lands conquered from the population of Arab descent. That’s why the Israeli narrative insists to such a degree on Amin al-Husseini, this character, blown up out of all proportion, who became the ex-grand mufti of Jerusalem.

On the Arab side, the most rational narrative—later we’ll mention the denialist escalations that are on the rise at present—may perhaps be summarized in these terms, “We had nothing to do with the Shoah. Anti-Semitism is not an established tradition for us, but a European phenomenon. Zionism is a colonial movement that really took off in Palestine under the British colonial mandate, even though there were earlier instances. In consequence, it’s a colonial implantation in the Arab world, on the model of what was seen in South Africa and elsewhere.” It’s the war between these two narratives that I explore in this book.

Is there a dominant Arab reading of the Shoah? In what respects is it specific and how does it differ from those in Europe or the United States?

There’s not a single Arab interpretation of the Shoah, just as there isn’t a single European reading either, even though there’s certainly more homogeneity in the perception of the Holocaust in Europe. However, even that is recent, since, as you know, the Shoah was not a very current theme in European news and education during the two decades that followed the end of the Second World War.

In the Arab world, the situation is far more diversified. That is chiefly the result of the existence of a great variety of political regimes in the Arab countries, with very different ideological legitimatizations. Similarly, very diverse—and even broadly antithetical—ideological currents traverse Arab public opinion.

In these last few years, there has been an escalation in the brutality of Israeli military operations—which have gone from being wars that Israel could present as defensive to wars that could no longer be presented that way at all—beginning with the invasion of Lebanon in 1982. That has been accompanied by an intensification of hatred in the Israeli-Arab conflict, notably because of the fate reserved for the Palestinians of the territories occupied since 1967.

In the face of growing criticism of Israel, including in the West, since 1982 especially, we have seen that state systematically resort to instrumentalization of the memory of the Shoah, beginning no later than the Eichmann trial in 1960. And that instrumentalization arouses, on the “opposing side,” a knee-jerk reaction that sometimes goes so far as to deny the Holocaust. The best indicator of this reactive quality is the fact that the Arab population which has received the widest education on the memory of the Shoah, the population of Arab citizens of Israel, has been prone to an absolutely striking explosion of denial these last few years.

To my mind, that very clearly illustrates the fact that denial in these cases corresponds more to a “gut reaction” out of political rancor, than to a true denial of the Shoah as is seen in Europe or the United States, where the deniers spend their time devising historical theories that don’t stand up to refute the existence of the gas chambers, etc.

Another indication of this difference is that within the Arab world where denial is riding high, there’s not a single author who has produced anything original on that theme. All the Arab deniers do is pick up theories produced in the West.

The political instrumentalization of denial as formulated by Ahmadinejad today was not used before in the Arab world, in the time of Nasser, for example. What does this development tell us?

The Islamic fundamentalism that has developed over the most recent decades, from the perspective of the Israeli-Arab conflict, carries an essentialist vision, even though it is not anti-Semitic in the strict racial sense of the term. It’s a vision that picks up the anti-Judaism that may be found in the Abrahamic religions that followed Judaism: Christianity and Islam. Those elements present in Islam are going to be pointed out to facilitate a convergence between this ideologically extreme current and Western denial.

What elements of Islam allow the realization of this anti-Judaism?

There are criticisms of Judaism within Islam and echoes of the conflict that arose between the Prophet of Islam and the Jewish tribes on the Arab peninsula. But it’s a contradictory background: we find anti-Christian and anti-Jewish statements in Islamic scripture. But at the same time, Christians and Jews are considered “people of the book” and may in consequence enjoy privileged treatment compared to other populations in the countries Islam conquered, populations which were forced to convert. The people of the book were not forced to convert and their religions were considered legitimate. Consequently, there is tension between these two contradictory dispositions.

I show in my book how the man who may be considered the main founder of modern Islamic fundamentalism, Rachid Rida, switched from a pro-Jewish attitude due to anti-Christianity—especially during the Dreyfus Affair, when he denounced anti-Judaism in Europe—to an attitude that, towards the end of the 1920’s, began to repeat an anti-Semitic discourse of Western inspiration, including the big Nazi anti-Semitic narrative attributing all kinds of things to the Jews in continuity with the fake Russian “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” including responsibility for the First World War. Then we see a graft occur between certain Western anti-Semitic discourse and Islamic fundamentalism which veers in that direction on this question because of what was happening in Palestine. Before the conflict turned ugly in Palestine, this same Rachid Rida tried to dialogue with representatives of the Zionist movement to convince them to form an alliance between Jews and Muslims to confront the Christian West as a colonial power. From that anti-colonialism that determines anti-Westernism, they were to move on to anti-Zionism, which, in the case of a fundamentalist religious mentality, combined very easily with anti-Semitism.

With that said, the signs of anti-Judaism that one finds in Islam, one finds a hundredfold in Christianity, and in Catholicism in particular, with the idea of the Jews as deicides, the Jews responsible for the death of Jesus, the son of God. This anti-Jewish charge contained in Christianity has, moreover, resulted in a persecution of the Jews in the history of the West incomparably worse than was the case in Islamic countries. We have seen, for example, how Jews of the Iberian Peninsula, fleeing the Christian Reconquista and the Inquisition, found refuge in the Muslim world, in North Africa, Turkey and elsewhere.

How have Hezbollah and Hamas used this rising tendency towards denial for political ends?

Rachid Rida’s discourse, integral to their ideologies, was present from the outset in Hamas and Hezbollah. Much more, by the way, in Hamas, which is an emanation of the Muslim Brotherhood in Palestine. The founder of the Brotherhood, Hassan El-Banna, was largely inspired by Rachid Rida.

In the case of Hezbollah, the discourse is presented through the slant of what was to come from political Iran: in Shiite fundamentalism originally, there is no source for an anti-Judaic dimension comparable to the one developed by Rida. It was to be elaborated along with the Iranian regime’s opposition to the West, to the United States and to Israel.

That said, what distinguishes Hamas as well as Hezbollah is that they’re mass movements, and, as such, they have a pragmatic dimension. As much as it suits Ahmadinejad to perform denialist one-upsmanship for reasons of state policy, these movements have to a large extent reduced the anti-Semitic discourse they previously expressed and which proved to be counter-productive.

What I understand from your book is that Holocaust denial has become a political instrument per se in the Middle East, whether one chooses to use it or not. How was this instrument integral to the political foundation of the Palestinian movement, especially with respect to the PLO?

The PLO, ever since the armed Palestinian organizations got the upper hand within it after 1967, very quickly came to understand that anti-Semitic discourse is bad in itself and altogether contrary to the interests of the struggle of the Palestinian people. Hence the insistence on the distinction to be made between anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism, which was the issue in a political battle within the Palestinian movement.

Conversely, what are the mechanisms of what you call the “positive” instrumentalization of the Shoah, as it emanates from Israel?

What may be the legitimatizations for the State of Israel? I’m not talking about questioning its existence, but about examining the legitimatizations that it gives itself. One has to confess that, apart from religious Zionists, the Biblical legitimatization convinces very few people! As for the justification that we find in secular Zionism as expressed most notably by Theodore Herzl, it’s a justification that does not take into account what is actually there where the “State of the Jews” is going to be created. The only justification he gives for that state is anti-Semitism in the West. He doesn’t concern himself with what’s already over there. Moreover, we know that at the outset the Zionist movement occasionally had very intense debates about the possible location for the Zionist state. Therefore, for the Zionist movement, it was a matter of inserting itself within a colonial undertaking and we find references to colonialism in Herzl’s book, including the idea of embodying a rampart of civilization against barbarism.

Colonial ideology having expired globally, it was necessary to find an alternative legitimatization: that’s when the instrumentalization of the Shoah began to intensify, especially from the beginning of the 1960’s with the Eichmann trial. Excellent work has already been done on this subject, particularly that of Tom Segev. It’s an absolutely remarkable work on the manner in which, within Israel itself, the question of the Shoah was to suddenly emerge and change character. The relationship to the Holocaust was to change from a relationship of contempt for the survivors to claiming that memory as a legitimatization for the State. Moreover, as a narrative, this legitimatization has been highly effective in the West on several levels, including in the relations maintained between Israel and the Federal Republic of Germany at a time when the German administration was stuffed with former Nazis. People frequently obscure the absolutely significant role Germany played in strengthening the State of Israel, notably by the reparations Bonn dispensed, not to the victims of Nazism, to the survivors of the genocide, but to the State of Israel presented as the survivors’ state. Consequently, this legitimatization of the State of Israel was to appear over time as a very high-value political instrument for that State, an instrument that today is overexploited.

The memory of the Shoah is invoked to counter every criticism. At times, this has reached the level of the grotesque as when Prime Minister Begin made his famous answer to Ronald Reagan during the siege of Beirut: Begin compared Arafat to Hitler then, at the very moment when it was the Israeli Army besieging Beirut and while many Israelis and other observers were instead finding parallels with the Warsaw Ghetto.

Does the parallel between the Nakba and the Shoah exist in the Middle East? In what respect does it reveal possible political developments?

At that level, there are two different aspects: the one that we’ve talked about, the war over the instrumentalization of the Holocaust, and there is what you could call the local version of competition between victims: “My tragedy is more important than yours.” On the Palestinian side, one may often read statements that assert that the fate of the Palestinian people has been worse than that of the Jews under Nazism. These are obviously altogether outrageous and absurd exaggerations, but we can easily understand what drives them. Moreover, we find this victims’ competition with respect to the Shoah in the case of other historical tragedies such as the Armenian genocide, for example.

At the same time, it is good to listen to former Knesset Speaker Avraham Burg’s remarks. He says out loud: “We are guilty of denying the genocides and the tragedies of others.” Confronted with a situation, where, in Israel, they deny the Nakba — and where it required the appearance of those who are called the “New Historians” and of post-Zionism for the official discourse of Nakba denial to be strongly questioned — there is not only a development of Holocaust denial on the Arab side, but also an escalation in their claims about the scope and the drama of their own tragedy. That can often lead to contradictory statements: on the one hand, Holocaust denial, a minimization of the crimes of Nazism, and, on the other hand, a discourse accusing Israel of reproducing the crimes of Nazism … It’s perfectly clear that it’s not logic that holds sway. It’s an ideological war that proceeds more through feelings and passions than through rational discourse.

In your conclusion, you present a rather optimistic analysis: “The progress made between Arabs and Israelis is significant when one considers the virtual impossibility of communication between them in the first decades following the Nakba.”

This progress has, in part, been a product of the PLO, which opened the way to a more rational attitude vis-à-vis the Shoah, the State of Israel and Israelis on the Arab side.

Connections between Arabs and Jews exist today and in the end must favor recognition of the Holocaust and of the Nakba. Israelis’ recognition of the latter is more difficult because it implies recognition of their own responsibility, with the direct implications you can imagine, and which would lead to an attitude radically opposed to that of Israeli governments up to now. Yet that recognition of the Nakba by Israel is today an indispensable step towards achieving a true settlement of this conflict that has gone on for too long.

—-

This interview first appeared Oct. 11 in Mediapart and was translated into English by Truthout, where it ran Nov. 9. It also appeared in November on ZNet.

See also:

LEBANON: THE 33-DAY WAR AND UNSC RESOLUTION 1701

by Gilbert Achcar, Alternative Information Center

World War 4 Report, September 2007

From our Daily Report:

Holocaust museum opens in Palestinian village on frontline of anti-wall struggle

World War 4 Report, April 22, 2009

Nazis planned Holocaust for Palestine: historians

World War 4 Report, April 11, 2006

Iran: protesters condemn Holocaust conference

World War 4 Report, Dec. 12, 2006

——————-

Reprinted by World War 4 Report, January 1, 2010

Reprinting permissible with attribution

The US-led Coalition's ongoing failure to admit to, let alone adequately investigate, the shocking scale of civilian deaths and destruction it caused in Raqqa is a "slap in the face" for survivors trying to rebuild their lives and their city, said Amnesty International a year after the offensive to oust ISIS. In October 2017, following a fierce four-month battle, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—the Coalition's Kurdish-led partners on the ground—announced victory over ISIS, which had used civilians as human shields and committed other war crimes in besieged Raqqa. Winning the battle came at a terrible price—almost 80% of the city was destroyed and many hundreds of civilians lay dead, the majority killed by Coalition bombardment. In a September 2018 letter to Amnesty, the Pentagon made clear it accepts no liability for civilian casualties. The Coalition does not plan to compensate survivors and relatives of those killed in Raqqa, and refuses to provide further information about the circumstances behind strikes that killed and maimed civilians. (Photo: SDF)

by Bassam Aramin, Sara Burke and Yaniv Reshef, Peacework

Combatants for Peace is a group of Israeli and Palestinian individuals who were actively involved in the cycle of violence between their peoples. The Israelis served as combat soldiers and the Palestinians were involved in acts of violence in the name of Palestinian liberation. Yaniv Reshef is a former infantry soldier in Israel’s elite Golani unit; he now lives within range of rockets launched from Gaza. Bassam Aramin served seven years in jail for planning an attack against Israeli soldiers. Two years ago, his seven-year-old daughter was killed when an IDF soldier shot her with a (US-made) rubber-coated steel bullet. Together with the 600 other members of Combatants for Peace, they have pledged to abandon violence and work together using creative nonviolent tools to build justice and peace—and playgrounds in memory of Abir Aramin. Peacework Co-Editor Sara Burke spoke with them on March 17, 2009, during their speaking tour of the Northeastern US.

What do you draw on for your commitment to nonviolent solutions? Is it part of a wider commitment to pacifism?

Yaniv: No, I am not a pacifist. It’s just that I am learning how to use a new way. In Israel, we’ve gotten too used to the use of force—especially our leaders, who are not evil but can’t let go of the old ways. With one hand they give a handshake, while they are thinking about what hill to grab, or what settlement to build, with the other hand. I was told in my unit, “If you can’t get something by force, use more force.”

Having made this commitment to find another way, I feel great. I heard a lecture by two members of Combatants for Peace, doing what Bassam and I are doing now, and I knew it might be the beginning of a beautiful friendship. And it’s still a beginning—I don’t want to burn out. I want this to be a long-term relationship.

I am not a full-time activist—this is only one part of my life. When I said this recently at a speaking event, one audience member was upset. She said, “You are only doing this part-time, but Bassam doesn’t have that luxury.” But Bassam is doing this so that he can have a life—so how is it going to help him if I don’t live mine? I’m trying to tell my new peace friends to be gentler, more welcoming. Sometimes on both sides, right and left, some kind of “holy justice” is invoked. If I have one piece of advice for peace activists, it is “Don’t be so holy.”

Bassam: Yes, I am committed to nonviolence in all situations. This comes from my experience, my life, my sufferings and the sufferings of my people. We live in hell. I wish I could bring Palestine with me on my shoulders to show people how we live. I want even my enemy to see my humanity. My power comes from seeing my enemy change, when she or he begins to recognize that in fact we have a common enemy, the Occupation.

What are you learning on your US tour? Have there been surprises?

Bassam: This is my third tour with Combatants for Peace, including visits both to the US and to Europe. Europeans tend to be better educated, and more open to learning about what is happening. Here in the US, sometimes people don’t even know who occupies whom—even though the US is so heavily involved. They need to know that the soldier who shot and killed my daughter was firing an American M-16, from an American Jeep. But when US Americans do learn the facts, sometimes it brings more action, as they are moved to say “Not in our name.”

Yaniv: Sometimes I am surprised, when we speak in synagogues, by how the liberal Jewish community here doesn’t know the facts. They don’t grasp that the settlements are built in a certain way specifically to prevent the building of a Palestinian state, and to prevent peace. But I shouldn’t be surprised, since they are simply believing their leaders, just as Israelis do. Even in Israel, people don’t understand—they think that the hand of peace has been extended to the Palestinians and that the Palestinians did not accept it. I myself am not against the Separation Wall, if it was on the legal line, but instead it is being used to create facts on the ground that make peace impossible.

At one synagogue where we spoke, they welcomed Bassam as their first-ever Palestinian guest. I said, “How can this be? We’ve been occupying them for forty years and you haven’t had a single Palestinian in your synagogue? As you’ve been celebrating Passover, year after year?”

What do you see as the greatest challenges, internal and external, to the peacemaking work that you and others are doing?

Yaniv: The challenge is not to hate, but instead to forgive your enemy, because then you don’t fear them any more. If you try to understand your enemy’s humanity, you become very strong and it helps both of you. It’s the most powerful thing you can do for yourself.

Bassam: In each of our societies, we need to face the deep fear, and to bring people awareness of what is really going on. Especially the Israelis, who know so little about the Occupied Territories. That is what we do with our talks, and it works. Once they understand, many of the Israelis we speak to change their minds, and become active in peacemaking. But the separation and the war make it more difficult. Combatants for Peace is often unable to get the permits that allow us to meet, and the group is financially very poor.

The last battle, in Gaza, made it more difficult for people to hear us. In Tel Aviv, one of our members was attacked in the street after a demonstration, but the police were helpful. In the Occupied Territories, of course, it is different—the Israeli army is more brutal.

We are at our best when we are trying to be as peaceful as we can get. People notice this—even the army notices it. One of our group leaders says, when we are demonstrating at the Wall, that we should not even remove a brick or a stone from the wall, so that we will not be seen as provoking hostility. When we act entirely peacefully, whether we are demonstrating, speaking, or helping with the olive harvest, we can educate some of the soldiers this way.

I don’t ask other Palestinians to join me in this work. Most of my friends are ex-prisoners, and are not ready to join — but they do agree that there is no solution to the problem through violence. I tell Hamas about our meetings, and they are amazed and incredulous. I tell them they are welcome to come to our meetings and see for themselves. None have come — so far.

—-

This article first appeared in the April 2009 issue of PeaceWork.

Resources:

Combatants for Peace

http://www.combatantsforpeace.org

See also:

PALESTINE: OBAMA’S FIRST FOREIGN POLICY CHALLENGE

New Standards on Self-Determination Needed to Resolve Dispute

by William K. Barth, OpEdNews

World War 4 Report, February 2009

——————-

Reprinted by World War 4 Report, January 1, 2010

Reprinting permissible with attribution

Taliban leaders confirmed that long-planned direct talks with the US took place in Doha, capital of Qatar. The Taliban said in a statement that their delegation met with US special adviser for Afghanistan reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad. The statement said the two sides discussed the prospects for an end to the presence of the foreign forces in Afghanistan, and the return of "true peace" to the country. These overtures come as the US is stepping up operations against ISIS in Afghanistan. In an August air-strike in Nangarhar province, the US claimed to have killed Abu Sayed Orakzai, top ISIS commander in Afghanistan. Earlier in August, more than 200 ISIS fighters and their two top commanders surrendered to Afghan government forces in Jowzjan province to avoid capture by Taliban insurgents, after a two-day battle that was a decisive victory for the Taliban. (Photo: Khaama Press)

“Everything Must Change So That Everything Can Remain the Same”

by George Caffentiz, Turbulence, UK

The Bush administration’s energy policy, with its evasions and invasions, has led to poverty, war and environmental destruction. But will Obama’s policy really be substantially different? Will this be change we can believe in? Turbulence asked George Caffentiz, a seasoned analyst of energy politics, to investigate.

Is President Obama’s oil/energy policy going to be different from the Bush administration’s? My immediate answer to this question will be a firm No, followed by a more hesitant Yes. The reason for this ambivalence is simple: the failure of the Bush administration to radically change the oil industry in its neoliberal image has made a transition from an oil-based energy regime inevitable, and the Obama administration is responding to this inevitability. We are, consequently, in the midst of an epochal shift and so must revise our assessments of the political forces and debates of the past with some circumspection.

Before I examine both sides of this answer, we should be clear as to the two sets of oil/energy policies being discussed.

The Bush policy paradigm’s premise is all too familiar: the “real” energy crisis has nothing to do with the natural limits on energy resources, but it is due to the constraints on energy production imposed by government regulation and the OPEC cartel. First, energy production must be liberalized and the corrupt, dictatorial and terrorist-friendly OPEC cartel dissolved by US-backed coups (Venezuela) and invasions (Iraq and Iran). Then, according to the Bush folk, the free market can finally impose realistic prices on the energy commodities (which ought to be about half of the present ones). This in turn will stimulate the production of adequate supplies and a new round of spectacular growth of profits and wages.

Obama’s oil/energy policy, during the campaign and after his election, has an equally familiar premise. As he presented on January 27, 2009, “I will reverse our dependence on foreign oil while building a new energy economy that will create millions of jobs… America’s dependence on oil is one of the most serious threats that our nation has faced. It bankrolls dictators, pays for nuclear proliferation and funds both sides of our struggle against terrorism.” In the long-term, this policy includes: a “clean tech” Venture Capital Plan; Cap and Trade; Clean Coal Technology development; stricter automobile gas-mileage standards; and cautious support for nuclear power electricity generation.

The energy policy he outlined in his budget proposal is supportive of a peculiar “national security” autarky. (This emphasis on self-sufficiency is all the more peculiar when it comes from an almost mythically pro-globalization figure like Obama.) Its logic is implicitly something like this: If the US were not so dependent on foreign oil, there would be less need for US troops to be sent to foreign territories to defend US access to energy resources. Obama treats oil in a mercantile way, as the vital stuff of any contemporary economy, similar to the way gold was conceptualised in the 16th and 17th centuries. Yet mercantilism has long been definitively abandoned as a viable political economy. In effect, he is calling for an autarkic import-substitution policy for oil while he is leading the main force for anti-autarkic globalization throughout the planet.

A Firm “No”

In Obama’s paradigm the key question for oil policy is US dependency on foreign resources. Such a prism obscures the consequence of the present system of commodity production. A failure to start from the simple fact that oil is a basic commodity and the oil industry is devoted to making profits leads to two significant misrecognitions. Firstly, the US government is essentially involved in guaranteeing the functioning of the world market and the profitability of the oil industry, and not access to the hydrocarbon stuff itself. Secondly, energy politics involves classes in conflict and not only competing corporations and conflicting nation states.

In brief, it leaves out the central players of contemporary life: workers, their demands and struggles. Somehow, when it comes to writing the history of petroleum, capitalism, the working class, and class conflict are frequently forgotten in a way that never happens with oil’s earthy hydrocarbon cousin, coal. Once we put profitability and working class struggle into the oil story, the plausibility of the National Security paradigm lessens, since the US military would be called upon to defend the profitability of international oil companies against the demands of workers around the world, even if the US did not import one drop of oil.

US troops will have to fight wars aplenty in the years to come, if the US government tries to continue to play—for the oil industry in particular and for capitalism in general—the 21st century equivalent of the 19th century British Empire. For what started out in the 19th century as a tragedy, will be repeated in the 21st, not as farce, but as catastrophe. At the same time, it is not possible for the US government to “retreat” from its role, without jeopardizing the capitalist project itself. As his efforts in Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan initially indicate, Obama and his administration show no interest in leading an effort to abandon this imperialist, market-policing role.

Thus Obama, along with the other supporters of the National Security paradigm for oil policy, are offering up a questionable connection between energy import-substitution and the path of imperialism. As logicians would say, energy dependence might be a sufficient condition of imperialist oil politics, but it is not a necessary one. This is Obama’s dilemma then: he cannot reject the central role of the US in the control of the world market’s basic commodity; whilst at the same time, inter- and intra-class conflict in the oil-producing countries is making the United States’ hegemonic role impossible to sustain. Therefore, as is implied in his approval of a troop “surge” in Afghanistan and the hunkering down of the US military in huge bases outside of Iraqi cities, Obama’s oil policy will be quite similar to Bush’s.

A Hesitant “Yes”

Up until now my argument has been purely negative, i.e., though Obama’s oil policy and Bush’s are radically different rhetorically, they will have much in common in practice. Obama’s goal of “energy independence” will not affect the military interventions generated by the efforts to control oil production and accumulate oil profits throughout the world. These interventions will intensify as the capitalist crisis matures and as the short-term, spot market price fluctuates wildly from the long-term price, and geological, political and economic factors create an almost apocalyptic social tension.

I do, however, see a major difference between Bush and Obama. The former was a status quo petroleum president, while the latter is an energy-transition president. In other words, Obama is in charge of a capitalist energy transition. It is similar to the successful one that, under Roosevelt, substituted oil and natural gas for coal in many places throughout the productive system in the 1930s and 1940s, and the unsuccessful one, under Carter, that failed to (re-)substitute coal, solar and nuclear power for oil and gas in the 1970s.

Eighty years ago, capital began to realize that coal miners were so well organized that they could threaten the whole machine of accumulation. This was an experience felt in the British General Strike of 1926 and the coal mining struggle in the US of the 1930s that led to the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Miners had to be put on the defensive by the launching of a new energy foundation to capitalist production. Then, 40 years on, President Carter despaired of putting the struggle of the oil-producing proletariat (especially in Iran) back in the bottle.

In the face of the failure of the Bush administration’s attempt to impose a neoliberal regime on the oil producing countries, the Obama administration must now lead a partial exit from the oil industry. It will not be total, of course. After all, the transition from coal to oil was far from total and, if anything, there is now more coal mined than ever before. Likewise, the transition from renewable energy (wind, water, forests) in the late 18th century to coal was also far from total. Indeed, this is not the first time that capitalist crisis coincides with energy transition, as a glance at the previous transitions in the 1930s and 1970s indicate. It will be useful to reflect on these former transitions to assess the differences between Bush’s and Obama’s oil policies. The different phases of the transition from oil to alternative sources include:

(1) repressing the expectations of the oil-producing working class for reparations for a century of expropriation;

(2) supporting financially, legally and/or militarily the alternative energy “winners”;

(3) verifying the compatibility of the energy provided with the productive system; and

(4) blocking any revolutionary, anti-capitalist turn in the transition.

These phases offer the kind of challenges that were largely irrelevant to the Bush administration, since it was resolutely fighting the very premise of a transition: the power of the inter- and intra-class forces that were undermining the neoliberal regime. Consequently, they will provide a rich soil for discussion, debate and planning in this period.

The subtitle of this piece applies to the “Firm No” side of my argument in a quite simple sense: the interests of the world market and the oil/energy companies will be paramount in the deployment of US military power. It also applies to my “Hesitant Yes” argument, though this time less directly—for the ultimate purpose of the Obama administration is (pace Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck) to preserve the capitalist system in very perilous times. It just so happens, however, that the “everything” that must change is more extensive than had ever been thought before.

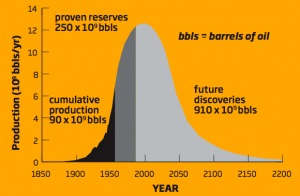

In regards to the first phase of the transition, we should recognize that there will be inter-class resistance to it from those who stand to lose. Of course, most “oil capitalists” will be able to transfer their capital easily to new areas of profitability, although they will be concerned about the value of the remaining oil “banked” in the ground. This transition has been theorized, feared and prepared for by Third World (especially Saudi Arabian) capitalists ever since the first oil crisis of the 1970s. But what is to be done with respect to the oil producing workers? After all, the “down side” of Hubbert’s Curve could, potentially, enable payback after a century of exploitation, forced displacements and enclosures in the oil regions.

Hubbert’s Curve is a graphical representation of the peak oil thesis. It is based on the observation that the amount of oil under the ground is finite, and the rate of discovery of new deposits increases to a “peak,” and then decreases, as new places to extract oil become rarer. During this decline the remaining oil becomes more valuable and could, if oil workers were in a strong enough position, be used to increase wages and pay reparations to the communities that have suffered during its extraction. Any demands to “make hydrocarbon fuels history” must take this potential into consideration.

The capitalist class as a whole is unwilling to pay reparations to the peoples in the oil-producing areas whose land and life has been so ill-used. Oil capital’s resistance to reparations is suggested by its horror, for example, at paying the Venezuelan state oil taxes and rents that will go into buying back land for campesinos whose parents or grandparents were expropriated decades ago. Capital wants to control the vast transfer of surplus value being envisioned in these discussions of transition, and without a neoliberal solution it is not clear that it can. Moreover, will the working class be a docile echo to capital’s concerns? Shouldn’t reparations be paid to the people of the Middle East, Indonesia, Mexico, Venezuela, Nigeria and countless other sites of petroleum extraction-based pollution? Will they simply stand still and watch their only hope for the return of stolen wealth snuffed out?

As far as the second phase of transition is concerned we should recognize that alternative energies have been given an angelic cast by decades of “alternativist” rhetoric contrasting them with blood-soaked hydrocarbons and apocalypse-threatening nuclear power. But let’s remember that the last period when capitalism was operating under a renewable energy regime, from the 16th to the end of the 18th century, was hardly an era of international peace and love. The genocide of the indigenous Americans, the African slave trade and the enclosures of the European peasantry occurred with the use of “alternative” renewable energy. The view that a non-hydrocarbon future operated under a capitalist form of production will be dramatically less antagonistic is questionable. We saw an example of this kind of conflict of interest in the protests of Mexican city dwellers over the price of corn grown by Iowa farmers that was being sold for biofuel instead of for “homofuel” (fuel for Homo sapiens).

In terms of phase three, we should remember that every energy source is not equally capable of generating surplus value (the ultimate end-use of energy under capitalism). Oil is a highly flexible form of fuel that has a wide variety of chemical by-products and mixes with a certain type of worker. Solar, wind, water and tide energy will not immediately fit into the present productive apparatus to generate the same level of surplus value. The transition will ignite a tremendous struggle in the production and reproduction process, for inevitably workers will be expected to “fit into” the productive apparatus, whatever it is.

Finally, phase four presents the nub of the issue before us. Will this transition be organized on a capitalist basis or will the double crisis opened up on the levels of energy production and general social reproduction mark the beginning of another mode of production? Obama’s energy policy is premised on the first alternative; we’ve examined some of the unpleasant prospects that follow. The scale of what is at stake requires us to keep the second alternative open. When we investigate the possibilities before us we must endeavor, with all our energy and ardor, to break with the premise that leads to “everything remaining the same.”

—-

George Caffentzis is a member of the Midnight Notes Collective and co-editor of Midnight Oil: Work Energy War 1973-1992 and Auroras of the Zapatistas: Local and Global Struggles in the Fourth World War. This article first appeared in the December 2009 issue of Turbulence.

See also:

“PEAK OIL” DECONSTRUCTED

Critique of the National Security Paradigm

World War 4 Report, September 2005

From our Daily Report:

Iraq and Iran de-escalate in prelude to OPEC summit

World War 4 Report, Dec. 20, 2009

Obama’s EPA silences dissent to carbon trading

World War 4 Report, Nov. 11, 2009

Obama denies White House to run GM

World War 4 Report, June 2, 2009

US oil profligance and third world petro-violence: our readers write

World War 4 Report, Jan. 24, 2007

Mexico: Calderon responds to “tortilla crisis”

World War 4 Report, Jan. 23, 2007

——————-

Reprinted by World War 4 Report, January 1, 2010

Reprinting permissible with attribution