The New Voice of Ecuador’s Indigenous Movement

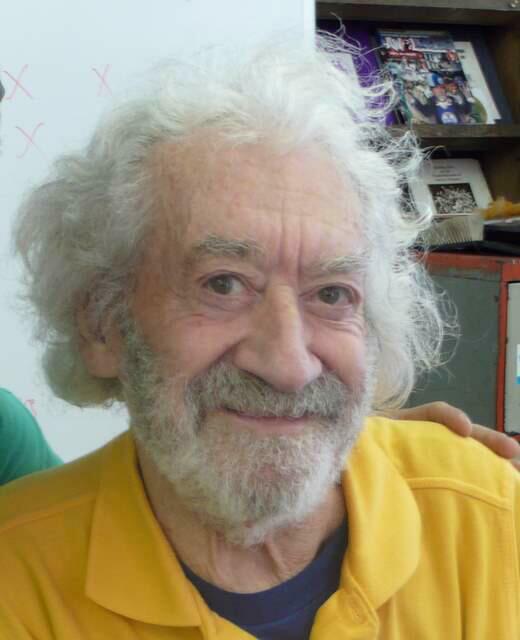

Marlon Santi” class=”image thumbnail” height=”100″ width=”99″>Marlon Santi

by Marc Becker, Upside Down World

The Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) has elected Marlon Santi to serve as its president for the next three years. Santi was elected by more than 1,000 Indigenous delegates gathered at Santo Domingo de los Tsa’chilas from Jan. 10-12, 2008, for the Third Congress of Indigenous Nationalities and Peoples of Ecuador.

Indigenous activists founded CONAIE in 1986 as a national federation to represent Indigenous interests to the government. CONAIE first gained broad international attention when it led a protest in June 1990 that shut down the country. In 1995, CONAIE helped found the political movement Pachakutik to run candidates for political office.

Santi was elected by consensus of the regional organizations CONAICE, ECUARUNARI, and CONFEINIAE that represent Indigenous peoples from Ecuador’s coast, highlands, and Amazon. He is a 32-year-old native of Sarayacu in the eastern Amazonian province of Pastaza. Sarayacu has long been a center of protest again petroleum exploration. After studying in Quito, Santi returned to Sarayacu where he was a tireless fighter against petroleum companies and corrupt governments. For his activism, Santi has received assassination threats. Santi vowed to continue CONAIE’s struggle against neocolonial domination.

Official delegates and other observers arrived to the Congress on the morning of Jan. 10 in a constant rain. The Congress opened with a traditional ceremony with the participation of several leaders of the different organizations, governmental representatives, members of the national assembly, and invited national and international representatives. Jaime Pilatuña, a yachak (shaman) of the Kitu Kara people, led a ceremony together with Hector Awavil, leader of the host Tsa’chila government, to create a harmonious space for the meeting. Children and women also made a presentation in the inaugural act. Juana Nenquimo, a member of Waorani nationality, spoke in four languages of their struggles against international oil, lumber and mining companies.

The Congress began with an analysis of Ecuador’s current political situation. Jorge Guamán, National Coordinator for the Indigenous political movement Pachakutik, and Mónica Chuji, an Indigenous delegate to the Constituent Assembly, presented reports on their political activities. Guamán stated that Indigenous peoples and nationalities in Ecuador have maintained the cultural, social, and political structures necessary to create successful government processes. They have formed these under the traditional Andean code of “ama llulla, ama shuwa, ama killa,” or don’t lie, don’t steal, don’t be lazy.

Luis Macas, outgoing CONAIE president, presented a report of his work during his three-year term. He referred to the Congress as a “minga” (a communal work party) to construct a new country that would belong to all Ecuadorians. “Even though some governments have done everything to divide us,” Macas said, “this Congress is a practical demonstration of our unity and brotherhood.”

Humberto Cholango, leader of the highland regional federation Ecuarunari, said that “this congress is of vital importance because CONAIE is responding to the poverty, exclusion, mistreatment, and discrimination we have received from the government with proposals for life.”

Constituent Assembly member Mónica Chuji read a letter from Alberto Acosta, president of the Constituent Assembly that is currently re-writing the country’s constitution, in which he states that “the assembly will fight for the recognition of the rights and achievements of all Indigenous peoples and nationalities.” Acosta called for a unity of all Indigenous organizations.

Acosta’s letter emphasized that Indigenous movements and its struggles against the oligarchy and colonial powers are of great transcendental importance to the social transformation that the country is experiencing. “The historical consciousness, the cultural inheritance of Indigenous peoples and nationalities are needed to build an inclusive and just society,” he said.

At the Congress, Indigenous leaders declared their opposition to any policies that would lead to an extraction of natural resources from Ecuador, particularly petroleum and water. Instead, these are elements of strategic importance to the development of the country.

A principle demand of the Congress was the recognition of Ecuador as a plurinational state. Delegates also appealed for the development of a social economy. Indigenous leaders called on the Constituent Assembly to change government structures and the political system to end social exclusion and inequality. They presented an Integral Agrarian Reform plan to redistribute land, eliminate inequality, and to stop environmental destruction.

Delegates to the congress ratified their unlimited support to the changes in Bolivia led by president Evo Morales. They identified those developments as an example for the entire continent of Latin American. Ecuarunari leader Humberto Cholango emphasized the Indigenous movement’s defense for the changes sweeping throughout the region. Cholango stated that Indigenous communities will not allow the oligarchy to destabilize their sister nations with the support of the United States government.

The Congress elected Miguel Guatemal as vice-president of CONAIE. In addition to Santi and Guatemal, CONAIE’s governing council for the next three years will be comprised of Humberto Martínez (Organization), Silvio Chiripuwa (Fortification), Luis Champis Dirigente (Territory), Fredy Paguay (International Relations), Fausto Vargas (Education), Agustin Punina Dirigente (Health), David Poirama (Youth), Norma Mayu (Women), Janet Kuji Dirigente (Communication). The new leaders were sworn in by a ceremony of thanks to the Pachamama (Mother Earth) led by the Yachakuna (Shamans) Jaime Pilatuña and Carlos Pichimba.

—–

This story first appeared in Upside Down World, Jan. 15, 2008

See also:

FOR THE “TOTAL TRANSFORMATION” OF ECUADOR

An Interview with Pachakutik Presidential Candidate Luis Maca

by Rune Geertsen, Upside Down World

WW4 Report, October 2006

/node/2574

From our weblog:

Ecuador: Correa puts down oil protests

WW4 Report, Dec. 26, 2007

/node/4865

——————-

Reprinted by World War 4 Report, Feb. 1, 2008

Reprinting permissible with attribution

Continue ReadingMARLON SANTI