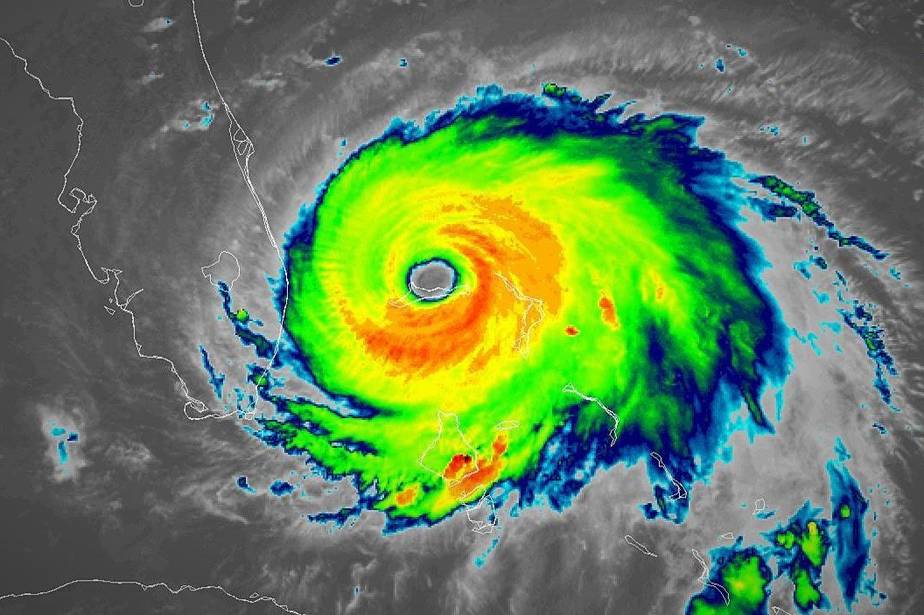

Hurricane Dorian’s slow, destructive track through the Bahamas fits a pattern scientists have been seeing over recent decades, and one they expect to continue as the planet warms: hurricanes stalling over coastal areas and bringing extreme rainfall. Dorian made landfall in the northern Bahamas on Sept. 1 as one of the strongest Atlantic hurricanes on record, then battered the islands for hours on end with heavy rain, a storm surge of up to 23 feet and sustained wind speeds reaching 185 miles per hour. The storm’s slow forward motion—at times only 1 mile per hour—is one of the reasons forecasters were having a hard time predicting its exact future path toward the US coast. With the storm still over the islands on Sept. 2, the magnitude of the devastation and death toll was only beginning to become clear. “We are in the midst of a historic tragedy in parts of our northern Bahamas,” Prime Minister Hubert Minnis told reporters.

Recent research shows that more North Atlantic hurricanes have been stalling as Dorian did, leading to more extreme rainfall. Their average forward speed has also decreased by 17%—from 11.5 mph to 9.6 mph—between 1944 and 2017, according to a study published in June by scientists at NASA and NOAA. Researchers don’t understand exactly why storms are stalling more, but they think it’s caused by a general slowdown of atmospheric circulation, both in the tropics, where the systems form, and in the mid-latitudes, where they hit land and cause damage.

Hurricanes are carried by global wind currents, “like a cork in a stream,” said Tim Hall, a hurricane researcher with NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies and author of the study. So, if those winds slow or shift direction, it affects how fast hurricanes move forward and where they end up.

How that slowing is connected to global warming is still an area of debate. There are different mechanisms at work in the tropics and mid-latitudes, but “in the broadest sense, global warming makes the global atmospheric circulation slow down,” said NOAA hurricane expert Jim Kossin, co-author of the June study.

He said scientists suspect the overall slowing of winds is at least partly due to rapid warming of the Arctic. The temperature contrast between the Arctic and the equator is a main driver of wind. Since the Arctic is warming faster than lower latitudes, the contrast is decreasing, and so are wind speeds.

Rising global temperatures also influence storms in other ways: A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, which means hurricanes can bring more rain, and warmer oceans provide additional energy that can make them stronger.

Hurricane Harvey dumped 60 inches of rain on parts of Texas in 2017 and stalled over the Houston area for days. Hurricane Florence stalled in 2018, flooding parts of coastal North Carolina. Kossin said Hurricane Sandy, in 2012, also took an unusual path that may have been affected by shifting global wind patterns, turning west and slamming into New Jersey instead of being carried eastward, out to sea and away from land, by prevailing westerly winds.

“Stalling hurricanes wreak much more havoc than those that blow through quickly,” said Hall. “Dorian definitely fits the pattern that we found in our paper.”

Dorian is the fifth Category 5 hurricane in just four years in the Atlantic, and only the 35th on record going back nearly a century.

Scientists have seen a trend toward stronger hurricanes in the Atlantic, although not an increase in the total number of storms, said Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

“The environment for all such storms has changed because of climate change. The oceans are warmer, especially in the upper 100 meters, which is most important for such storms,” Trenberth said. “This makes available more energy via water vapor for the storms and makes for more activity: more intensity, bigger and longer lasting storms, with heavier rainfalls.”

Condensed from Inisde Climate News

See our last post on the mega-storm phenomenon.