In an effort to quell controversy, liberated Puerto Rican political prisoner Oscar López Rivera has declined to be an honoree at New York City’s upcoming Puerto Rican Day Parade, writing in a statement to the Daily News: “The honor should not be for me; it should be bestowed on our pioneers who came to the United States and opened doors. It should go for activists and elected officials who fight for justice and a fair society.” This comes after Goya Foods and other traditional sponsors of the parade had pulled out under pressure of a media campaign portraying OLR as a “terrorist.” The New York Post, of course, has been particularly aggressive, and national right-wing media like Breitbart had also piled on.

Surprisingly, some otherwise progressive voices have likewise joined this chorus. Community activist Cormac Flynn in Manhattan’s The Villager makes a deeply flawed analogy between the honoring of OLR and the statues of Confederacy leaders now coming down across the South—as if there were any equivalency between López Rivera’s National Liberation Armed Forces (FALN) and the Slave Power of the Old South, as if the violence of the oppressed and that of the oppressors should be judged the same way.

Juan Gonzalez emphasizes this point in a Daily News column, “Puerto Rican New Yorkers don’t need approval to march in support of Oscar Lopez Rivera.” He compares the Puerto Rican militants of the FALN’s day to “the IRA’s armed campaign against British rule in Ireland, or Nelson Mandela and the ANC’s war against white rule in South Africa, or Menachem Begin and the Irgun’s guerrilla campaign against British rule in Palestine.” And he notes that exponents of all these struggles have been honored in NYC parades:

Mandela, of course, received a ticker tape parade down Broadway in 1990.

Begin became the first Israeli prime minister to attend New York’s Salute to Israel Parade in 1978, with barely a mention in the city’s press that he commanded the Irgun when it bombed the King David Hotel in Jerusalem in 1947, killing more than 90 people.

As for the IRA, in 1983 New York’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade named as its grand marshal longtime IRA leader Michael Flannery. Some politicians like Sen. Pat Moynihan chose to boycott, but Mayor Koch and Gov. Mario Cuomo participated, anyway.

However, saying that the violence of the oppressed and oppressor shouldn’t be judged the same way is not to say that the latter shouldn’t be judged at all. And you don’t have to be a part of the reactionary “anti-terrorist” or double-standard crowd to legitimately ask if OLR has actually repudiated (as opposed to merely renounced) that FALN’s terroristic tactics, which did indeed claim civilian lives. The two worst attacks were that at Manhattan’s historic Fraunces Tavern in 1975 (four dead) and at the Mobil Oil Building in 1977 (one dead). Three police were also seriously injured in coordinated blasts at four government buildings around New York on New Year’s Eve 1982. It should be noted that OLR himself was never charged in relation to such attacks, and the FALN’s imprisoned militants all (at least) renounced violence when the organization was formally disbanded in 1983.

OLR writes in his Daily News statement:

We must shift the focus. We cannot let people who are unfamiliar with Puerto Rican history define the narrative and experiences of our community. I want to repeat what I have said in many interviews, both in prison and since my release. I personally, and we as a community have transcended violence — it’s crucial for people to understand that we’re not advocating anything that would be a threat to anyone.

Popularly called a “political prisoner,” OLR more correctly considered himself a “prisoner of war,” under terms of the First Protocol of the Geneva Convention, as he was detained in a conflict against colonial occupation.

This opens the semantic question of what is “terrorism.” Juan Gonzalez in his column somewhat problematically states of the Irish Republican Army, African National Congress and Irgun: “All were both terrorists and freedom fighters at the same time. Even those who condemned their methods could admire their goals.” Palestinians would certainly take issue with the notion that Irgun were freedom fighters. More fundamentally, this construction sidesteps the whole question of the indivisibility of ends and means.

It is nearly forgotten that the ANC’s armed wing did indeed carry out some attacks that could legitimately be considered terrorism in the bitterest days of the anti-apartheid struggle. The celebration of Nelson Mandela upon his death in 2013 exhibited much historical revisionism about the fact that the US position was for years to stigmatize him as a “terrorist.” Even worse was the absurd hypocrisy from right-wing politicians who sought to exploit his legacy to bash Cuba as a dictatorship. Mandela himself saw Cuba as a fraternal state that stood by the anti-apartheid struggle during the long years that the US demonized it as “terrorist.”

And—tellingly—political exiles from the United States are still taking refuge in Cuba today. One is the FALN’s William Morales. Another is veteran Black Panther Assata Shakur. Many other former Panthers remain behind bars in the US, such as Assata’s old comrade Mutulu Shakur, and Russell ‘Maroon’ Shoatz. There arguably needs to be a truth and reconciliation process over the period of armed left militancy and state repression in the US from the late ’60s through the early ’80s, based on recognition that such figures are prisoners of war.

Which brings us to a final, critical point, nearly universally overlooked. Gonzalez notes that the current financial crisis in Puerto Rico has led to a dangerous erosion even of the island’s actual self-governance (itself falling short of real self-determination): “So here we are in 2017, with Puerto Rico’s economy near collapse, and a control board imposed by Congress now ruling the island’s affairs in classic colonial style.”

The oppressive conditions that led to armed militancy in the United States in the 1960s have in many ways only gotten worse since then. And amid all the terrorist-baiting, there has got to be a reckoning with this.

Photo via PM Press

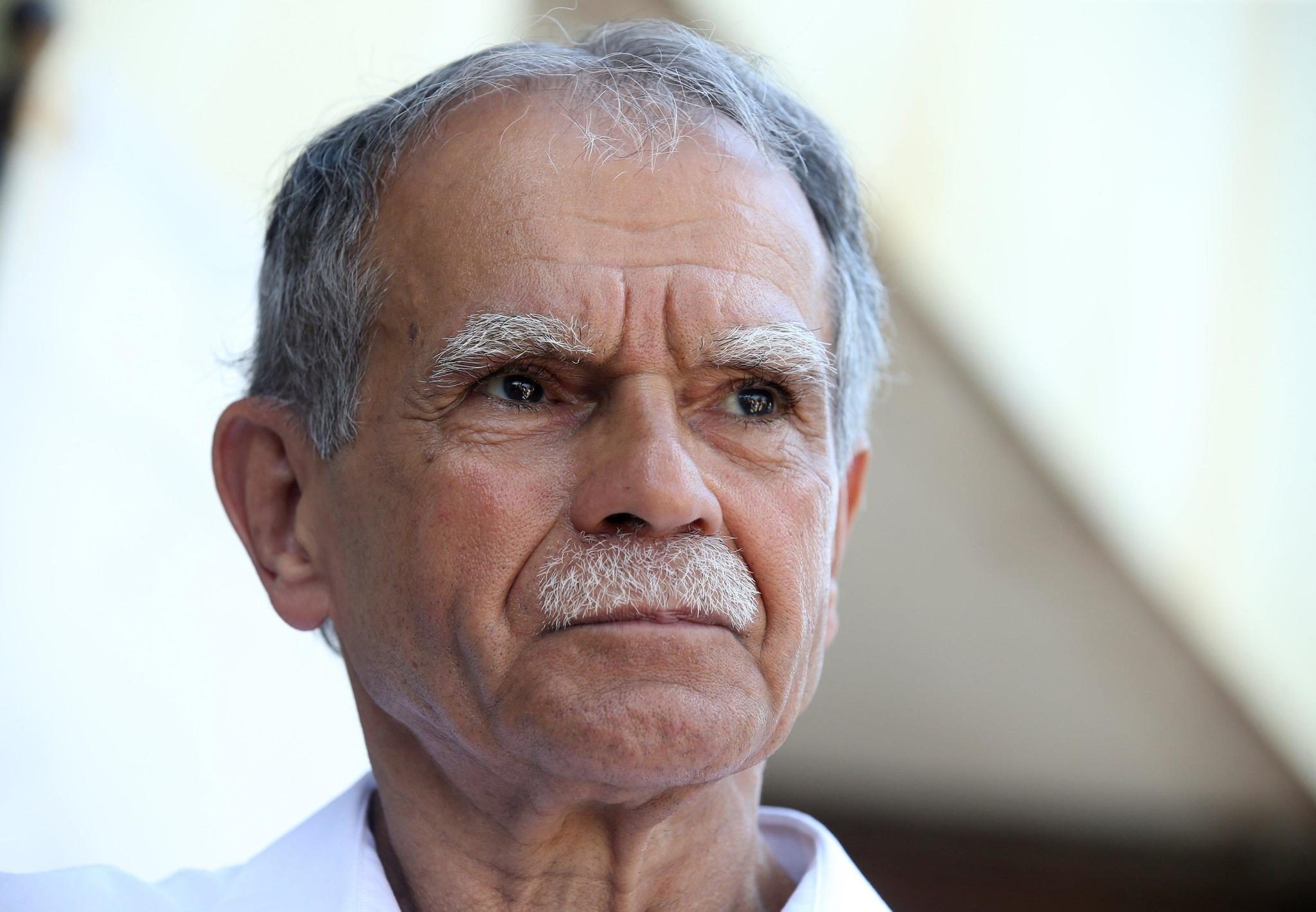

Mutulu Shakur speaks

Mutulu Shakur, who has an advanced form of cancer, is making up for lost time with his family after the Black liberation activist was released on parole from a 60-year prison sentence in December.

“I’m so happy to be free,” Shakur, Tupac Shakur’s stepfather, told NBC News. “I fought hard every day that I was incarcerated. I have a lot to do, hoping that society gives me another swing at it. But my life is an example of what could happen. I am very hopeful.”