Stuart Christie, the legendary anarchist and anti-fascist militant most notorious for his 1964 assassination attempt on Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, died Aug. 15 at his home in East Sussex, England. The cause of death was given as lung cancer. At 74, Scottish-born Christie was still an international icon of the anarchist movement, seen as a bridge between the era of “classical” anarchism in the early 20th century and the resurgent radicalism of the New Left that emerged in the 1960s.

As a youth in Glasgow, he initially got involved in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, through which he was introduced to anarchist currents in the ban-the-bomb movement. Relocating to London, he fell into the orbit of Albert Meltzer, a prominent veteran of the pre-war anarchist movement in England who had actually met Emma Goldman when she toured the United Kingdom in 1935. Meltzer would become Christie’s mentor and lifelong friend.

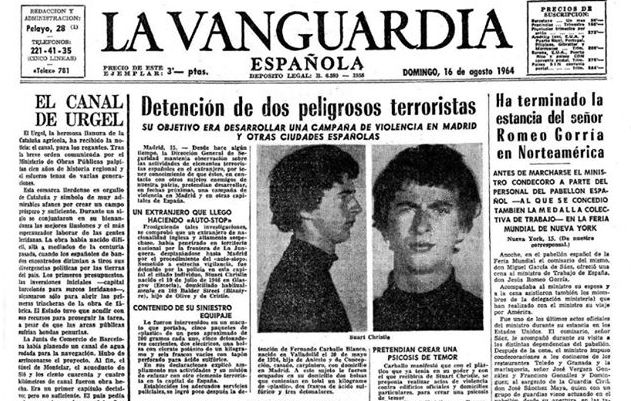

In 1964, at the age of just 18, inspired by the legacy of anarchist heroism in the Spanish Civil War, Christie established contacts in the underground resistance movement in Franco’s Spain, and volunteered for an assassination plot on the dictator. He got as a far as Madrid before he and his Spanish co-conspirator were discovered and arrested. By a popular account (which Christie later denied), the explosives intended for the assassination were hidden under his kilt.

Christie was roughed up in detention but received relatively light treatment, probably due to his British citizenship. However, he was forced to watch through a two-way mirror as his comrade Fernando Carballo Blanco was tied to a chair and brutally tortured.

They were both convicted on “terrorism” charges and sentenced to 30 years imprisonment. The two served three years together at the famously brutal Carabanchel Prison outside Madrid. Christie received clemency and was released in 1967—again, he believed, thanks to British citizenship at a time when the UK was financially supporting the Franco regime. Carballo Blanco would only be released upon Franco’s death in 1975.

Back in Britain, Christie founded Anarchist Black Cross, a support group for anarchist political prisoners worldwide which remains active today.

He was also held to be the key figure behind the Angry Brigade, an underground armed left cell that carried out a series of bombings that caused property damage at several targets around London in the early 1970s, including the US and Spanish embassies. In 1972, he faced criminal charges for his supposed involvement in the Angry Brigade as one of the “Stoke Newington Eight,” but was acquitted. He would not, however, renounce the group’s tactics, quipping, “General Franco made me a terrorist, and Edward Heath made me angry.”

After the trial, he retreated to the Orkney Islands, where he established Cienfuegos Press, a small anarchist publishing house, and dedicated himself to writing. He co-authored The Floodgates of Anarchy with Albert Meltzer. He later wrote The Angry Brigade: A History of Britain’s First Urban Guerilla Group, and a memoir, The Christie File. He was still maintaining a successor small press house, Christie Books, at the time of his death.

Looking back on his career, Christie told the Scottish radical journal Bella Caledonia in 2008:

Where are today’s angry young people? They can’t all have been muzzled by debt or seduced by the idea that freedom is somehow linked to property ownership. What if anything are they doing to vent their anger about Britain’s criminal military adventures in Iraq and Afghanistan, the blatant infringement of habeus corpus, the stifling of free speech, the medievalising of the public realm with the so-called anti-terrorism laws which allow police officers to shoot suspects dead and detain people without trial, charge or even explanation. Or to halt the present onward march to an undeclared permanent state of emergency—and the constant, grinding erosion of our liberties.

But idealism—the human search for something beyond ourselves, a star to follow—has not died, nor will it. You can see it today in the anti-globalisation, ecological as well as human and animal rights movements—even though they are still fringe activities—but then again, perhaps our activities in the sixties/seventies were probably fringe too!

Sources: Bella Caledonia, Rojo y Negro, VilaWeb, PM Press, 325, London Times, London Times, Blantyre Project, BBC Mundo

Image via Bella Caledonia